Bethesda Terrace

The Minton tile ceiling design is made up of 15,876 individual encaustic tiles. These are divided between 49 panels. There are two repeated panel designs that differ only in the central motif being either large or small. Each panel is made up of 324 tiles. The tiles were fixed to cast iron back plates by a simple brass ‘dovetail bolt’. This ingenious fixing used a special slot in the back of each tile that was produced by inserting a wedge-shaped piece of wood that burnt out during firing. The head of the bolt could then be fitted and cemented for extra strength. Once in place, the protruding bolt was threaded through the back plate and secured with a nut. Each back plate was held in place by a grid of structural cast iron work attached to the Arcade stone and brickwork.

This article provides an introduction to the commissioning and restoration of the stunning Minton tile ceiling at Bethesda Terrace rather than the detailed story or a research report. That information will form the basis of future articles and formal papers (and is subject to approval in part from Central Park Conservancy as well as other key archives, collections and organisations in both the UK and USA). I also offer an initial insight into my own research perspective, context and journey to date.

Having grown up in The Potteries I was inspired by Stoke-on-Trent’s ceramic legacy from an early age - probably ever since watching family and friends turning crockery over wherever we went to see if it came from our home town! As I grew older and began to understand the truly staggering global dimensions of this unique creative industries story, I wanted to find out more and more.

From the rich seam of visionaries and entrepreneurs to the myriad of crafters and grafters involved in making and taking local products to a voracious international market, many contributed - but most suffered (from very poor working conditions and low wages).

To this day fine products made in Stoke-on-Trent feature in museum collections in every part of the globe, and architectural ceramics - in particular tiles - form an integral part of some of the most important palaces, religious buildings and houses of parliament. Much of my professional practice is committed to exploring and promoting new ways to unlock the contemporary cultural value of this worldwide historic ‘collection’ in relation to local renewal opportunities and community benefit for The Potteries. The City and its people need and deserve a ‘return on their investment’.

I have been mildly obsessed with the unique Minton tile ceiling at Bethesda Terrace in Central Park, New York since stumbling upon it by chance in 2007. As someone with an interest in and some knowledge of the more significant historic ceramic exports from Stoke-on-Trent, I was surprised and intrigued that I had not heard of this important and prestigious commission before. Interestingly, I've since found that not many other people from The Potteries (or elsewhere) know about this commission or much about its truly amazing story. This is even more intriguing given that Bethesda Arcade’s Minton tile ceiling is without doubt one of the most visited and photographed architectural ceramics in the world.

During the last 5 years I have conducted research into the original mid-1860s commission as well as the relatively recent restoration work that culminated in its public re-launch in March 2007. Three individuals in particular have enabled me to take significant steps forward with my enquiry - Lynn Pearson, David Malkin and Chris Cox. The Tiles and Architectural Ceramics Society has offered wonderful support throughout including a most welcome Research Grant in 2012 that enabled me to undertake a unique and valuable research residency with Central Park Conservancy hosted by Matt Reiley, Associate Director of Conservation & Preservation.

The story begins in 1858 when Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux created the Greensward Plan to improve and expand Central Park. British architect Jacob Wrey Mould worked closely with them both, designing many notable features including Belvedere Castle, a great number of bridges and Bethesda Terrace - the formal architectural centrepiece of Central Park. Mould created the detailed designs for the ceiling and floor tiles to adorn Bethesda Arcade.

Mould studied the Alhambra in Granada, Spain under Owen Jones and later co-designed the Turkish Chamber of Buckingham Palace with his influential mentor. During the 1840s, Jones had worked with many of the major companies including Maw & Co., Blashfield and Minton. Mould’s subsequent designs were often influenced by his appreciation of the Moorish style of architecture. He also inherited some relationships with British tile and mosaic firms including Minton & Co. from Jones.

Sadly, only a handful of Mould’s original hand-coloured drawings for Central Park exist or are held in archives today. However, the meticulous records produced by the Board of Commissioners for Central Park offer some interesting information relating to the approvals and contractual detail. The detailed designs were presented as a monochrome wood block print (by J.W. Orr and signed by C. Vaux) in the Annual Report 1863. The Board’s Annual Report 1865-67 states “A Contract has been entered into for the iron-work for the ceiling of the interior of the Terrace, and also for the encaustic tile for the ceiling and for the floor of the same structure.” Later meeting minutes provide evidence that Miller & Coates - a specialist import company based at 279, Pearl Street, Manhattan - had been engaged to broker the order with Minton & Co. (Stoke-upon-Trent, England).

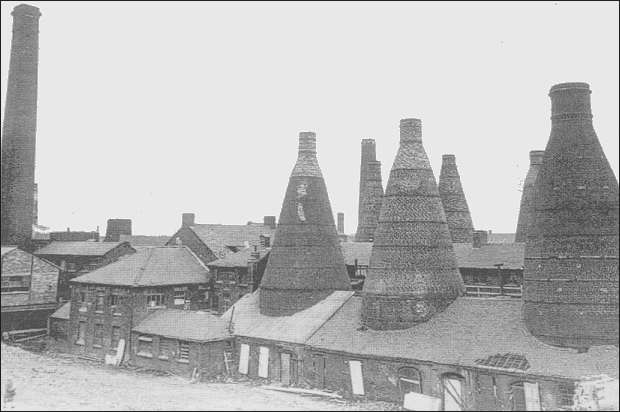

The tiles were produced at Minton’s London Road site (Figure 1) and exported in batches between 1865 and 1867. No specific details of this order are believed to exist or be held in archives. The tiles would have been packed in straw lined basket-crates and loaded onto narrowboats (probably Anderton & Co.) moored against the manufactory on the Newcastle-under-Lyme Canal. This precious cargo then began its epic journey from The Potteries by travelling the short distance via a tunnel under Church Street and past the busy Spode works to join the Trent & Mersey Canal. It would have taken between 10-12 days to follow the busy navigation to Runcorn Gap. The crates were then loaded onto Mersey sailing flats and transported down river to their designated export dock in Liverpool. Dukes Dock is the most likely in this case (next to Albert Dock). During the second half of the 1800s, steamships began to replace sailing clippers for crossing the Atlantic. Sail could take on average 35 days (sometimes a lot longer) but steam could cut that travel time in half and offer a more reliable and regular service. Again, lack of import records for specific goods means it is difficult to ascertain mode of crossing, shipping line or exact times for the tiles. Pearl Street based importers Miller & Coates were close to Piers 17 and 18 (formerly 22 and 23) in the area known as South Street Seaport today. Many famous packet lines operated from here in the shadow of Brooklyn Bridge. The final leg of the journey was likely to have been by horse and cart - possibly following a direct route uptown that became Broadway, the oldest north-south thoroughfare on Manhattan.

The Minton tile ceiling design is made up of 15,876 individual encaustic tiles. These are divided between 49 panels. There are two repeated panel designs that differ only in the central motif being either large or small. Each panel is made up of 324 tiles. The tiles were fixed to cast iron back plates by a simple brass ‘dovetail bolt’. This ingenious fixing used a special slot in the back of each tile that was produced by inserting a wedge-shaped piece of wood that burnt out during firing. The head of the bolt could then be fitted and cemented for extra strength. Once in place, the protruding bolt was threaded through the back plate and secured with a nut. Each back plate was held in place by a grid of structural cast iron work attached to the Arcade stone and brickwork. The metal work was made in Brooklyn and the stone was sourced in Connecticut.

After more than a century of success, Central Park began to suffer from neglect and decline during the latter half of the twentieth century. By the late 1970s and early-1980s it had become dangerous for the general public to use. Itinerants, prostitutes and drug users frequented Bethesda Terrace and Arcade - it had become a no-go area.

In 1980 the new non-profit Central Park Conservancy was formed and increasingly took over responsibility for park improvements and management during the following decade.

In 1984 the tile ceiling panels were all removed due to safety concerns and structural instability relating to severe corrosion of the cast iron that held the tiles in situ from water and road salt infiltration.

In 1997, Central Park Conservancy began the restoration of two pilot panels. This eventually led to a re-think in relation to the overall conservation approach due to the damage inflicted when completely dismantling each panel and separating individual tiles from the back plate and each other. The tiles faces were generally in good to excellent condition. It was decided that the other panels should be treated as a whole, keeping the originals relationally intact and with as little disturbance as possible. Although some tiles would need to be repaired and replaced, the plan was to concentrate efforts on the back plate including the fixings.

After painstaking tests, experiments and the truly heroic delivery of this massive and complex conservation programme, the new approach resulted in the replacement of structural metal work and fixings for each of the remaining 47 panels. Individual tiles from the two dismantled pilot panels were used to replace irreparably damaged tiles within these remaining panels. This resulted in the need to make nearly 2000 reproduction tiles in order to re-create the two panels which had been used as pilots, and to provide spares or ‘attic stock’.

To explain this part of the story properly you need to understand the role of TACS member David Malkin in the restoration. He was involved in the project from the early 1980s and was instrumental in the eventual supply of the replacement encaustic tiles required. David was the last Managing Director of Malkin Tiles. He then became Head of Public Relations for H.&R. Johnsons, Stoke-on-Trent, England when they bought his family company in 1968.

In the early years, David offered specialist advice to the conservation professionals assessing the programme. He also supported high profile campaigns promoting the restoration project and the significant investment needed to achieve it. Eventually, in 2001, sufficient funds had been raised and final plans were agreed. David had moved to the United States and founded Tile Source Inc. He was invited by Central Park Conservancy to oversee the supply of reproduction encaustic tiles.

David had previously been a major influence on H.&R. Johnsons’ decision to re-start encaustic tile production in Stoke-on- Trent in response to a series of prestigious and high value commission opportunities including the United States Capitol Building, Smithsonian Institution (Washington DC) and The State Capitol, Albany, New York. This specialist niche production facility was eventually sold off and became an independent company trading as Maw & Co. (interestingly a reincarnation of the name of Minton’s former competitor). Brian Joyce and his team worked from a production facility in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent and made the tiles required, based on the remaining originals.

The final mammoth task was to re-install the 49 refurbished panels (and skylight) in the Arcade (more than 50 tons). The reproduction tiles were used to recreate two new panels now located in the east loggia and discernable only to a keen eye. The majestic restored Minton tile ceiling was re-opened to the public with a prestigious launch event in March 2007.

So this fabulous story concludes (thus far) with the remarkable contemporary transatlantic re-connection between Stoke-on-Trent and New York nearly 140 years after the original commission. The unique creative skills and high quality production still to be found in The Potteries were sought by one of the most prestigious clients in the world - yet again. In the case of Bethesda Arcade, history repeated itself with high quality encaustic tiles being produced in the ‘Ceramic City’ and delivered to Manhattan - not by narrowboat and ship this time but transit van and freight plane from Manchester Airport!

Finally, you may have registered earlier in the piece that the Board of Commissioners for Central Park approved encaustic tiles for the ceiling and for the floor. The original floor tiles failed within 35 years due to damp conditions and damage from a ruptured sewerage pipe serving new ‘rest rooms’ installed either side of the Arcade rear steps (according to records). No original drawings are known to exist and no other specific information can be found in annual reports or Board records. However, fragments of the original tiles have been found beneath the existing floor. It is believed that the original floor was simply broken up and used as part of the base for the new quarry tile and granite block floor laid in 1911. The photograph included here shows some of the fragments informally catalogued during my residency last year (Figure 10). Intriguingly, the designs appear to also be bespoke and unique (and very different to the ceiling designs). They are back-stamped “Minton Hollins” so could be slightly later and produced in the then newly opened state-of-the-art Shelton Old Road works designed by the important Potteries’ architect Charles Lynam. Matt Reiley (Associate Director of Conservation and Presentation, Central Park Conservancy) and myself continue our conversation about the original floor tiles and further research is planned.

Information has been gathered from material held by:

USA: Central Park Conservancy (Chris Nolan, Matt Reiley, John Harrigan, Marie Warsh), New York Public Library, New York City Municipal Archives (Leonora Gidlund), New York City Parks & Recreation (Parks Library - Kaitilin Griffin), Association for Preservation Technology International (APT Bulletin - Peter Champe, Mark Rabinowitz).

UK : David Malkin, Staffordshire Film Archive/Staffordshire University (Ray Johnson), National Waterways Museum in Ellesmere Port, Craven Dunnill Jackfield (Chris Cox).

Acknowledgements

Credits for images: Fig. 1 Staffordshire Past Track (www.staffspastrack.org.uk), Figs. 2 - 10 Danny Callaghan (thanks to Central Park Conservancy & City of New York Parks & Recreation / Parks Library).